Documentation, then and now

Lately I’ve become fascinated with the mechanics of being a scholar. Or, more precisely, the mechanics of scholarly research.

Along this vein, I’ve read two pieces recently that have altered the way I think about scholarship and the intellectual labor of academics. The first is a short piece by C. Wright Mills that appears as an appendix to his The Sociological Imagination (1959). The second is Umberto Eco’s How to Write a Thesis (1977), which the New Yorker calls, “A Guide to Thesis Writing That Is a Guide to Life.”

It’s remarkable how many parallels to today can be drawn from these pre-internet guides to research. For in reading Eco, I discovered that documentation is as documentation was, which is to say that the craft of bibliographic citation and its role in humanities scholarship offers valuable lessons for those creating digital projects in the humanities today. Eco repeatedly refers to citations as “documentation,” which points to the way in which academics and students are accustomed to meticulously documenting the sources with which they constructed their argument in the form of a bibliography. Why, then, is it so uncommon to find a digital humanities project that similarly documents the technologies and systems used to construct it? Or when it started and when it ended, who contributed and who funded it? Why does it seem like the default position is that a digital project speaks for itself?

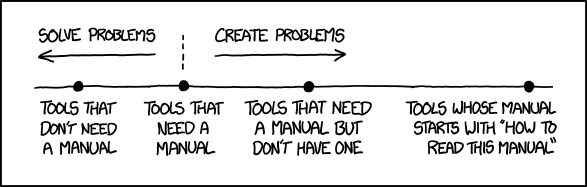

Writing software documentation is a struggle, apparently (there is a whole conference devoted to doing it well). It is thankless, an afterthought, something that we all know should be done but rarely is; writing project documentation is like taking the minutes at a meeting. Somehow, this is deemed “extra” labor that falls outside the core of the scholarship entailed in the project. Yet, if all we do is make, make, make and never document the making—are we scholars or artists? Is there a difference? Digital humanists ask themselves if a prototype can be a theory, which is a nice idea, but I’m starting to think that it cannot be anything (scholarly) unless it is documented.

A key lesson I’ve learned from reading Mills and Eco with this backdrop has to do with the deliberateness of scholarship. It is, shall we say, disciplined. Often we try to evade the tedious labor of academic research (to avoid “taking the minutes”) by discussing ways to automate x, y, z. If we just use Zotero to capture citations while we jump from database to database, it will free up our time for more real research activities. But I’ve come to realize that the very act of engaging with the tedious aspects of scholarship is what separates academics from everyday researchers. To state the obvious: methodology is methodical, and you can’t just run around haphazardly plucking materials that you’ve stumbled upon and call it a day. But being methodical takes time—time that today’s overburdened students lack. The graduate students I meet with struggle with feeling very un-methodical, so we talk about getting organized and keeping a research log. Zotero helps. But nothing I say can give them what they need most: more hours in the day to spend with the materials they’ve already found.

Here, we should also pause to consider Eco’s comments on the “vertigo of accumulation”:

“There are many things I do not know because I photocopied a text and then relaxed as if I had read it” (Eco 1977) pic.twitter.com/MjBynI9q0D

— Roxanne Shirazi (@RoxanneShirazi) September 11, 2016

“If you are not in a great hurry…” I have never met a graduate student who is not in a great hurry.

Mills’s piece is centered around the idea of keeping a master file, a sort of literary journal kept by a scholar to document her interests, research agenda, ideas, imaginations, theories, etc. It sounds an awful lot like a lab notebook, thinking along the lines of the library as the laboratory for the humanities. Mills talks at length about the ways in which reorganizing these files, reshuffling these ideas, can be generative and imaginative. And yet. It requires a deliberate and meticulous method of keeping everything organized.

Disciplined. Deliberate. Meticulous. Methodical. I’m reminded of the advice Robin D. G. Kelley received once from Cedric Robinson: “Scholarship is not dispassionate, but it is deliberate and systematic…”

Reading these two works has also been instructive of the ways in which scholarship presents itself as manual labor, or to use Mills’s term, “craft.” Imagine a time study analysis of a humanities scholar at work in an archive: how many minutes spent filling out paper call slips, waiting for boxes to be paged, sifting through documents only to find nothing of any real use to the project at hand? How many dead ends of books consulted, documents reviewed, only to achieve negative affirmation that, no, in fact, that information does not exist. (At least not here.) Eco recreates a thesis research exercise in which he takes three afternoons in the library just writing down citations. No photocopies, no reading, no extensive notes. Just compiling a bibliography of items to find.

Painstaking. We take pains to go through the process, to navigate the bureaucracy of “the archives” because, more often than not, we have no choice in the matter. Yet perhaps we need this built-in time to slow down, to temporarily pause the accumulation of sources and just sit with our craft for a moment.

***

Eco, Umberto. How to Write a Thesis. Cambridge: MIT Press, 2015.

Mills, C. Wright. Sociological Imagination. New York: Oxford University Press, 2000.