Day of Remembrance, 2016

Today is the annual “Day of Remembrance,” in which the United States reflects on the atrocity we now affably refer to as Japanese American Internment. I recently deposited my thesis, which touches on the topic, so I thought I’d post here the preface I wrote explaining the background of my project. If you’d like to read more, it’s available in its entirety in CUNY Academic Works.

***

On May 6, 1942, Dr. Peter Marie Suski assigned my great-grandfather, Willis M. Hawley, power of attorney to manage his personal affairs when he and his family, along with 120,000 Japanese Americans, were forcibly removed from the Pacific Coast to one of ten U.S. government internment camps. The two men began a regular and frequent correspondence that would continue throughout the war and beyond, producing at least 566 pages of letters between 1942-1960. Dr. Suski and Mr. Hawley wrote as friends, book collectors, and scholars of the Japanese and Chinese languages, and their letters comprise a richly detailed source for biographical and social history. Though densely written and, at times, highly technical in nature, the correspondence contains valuable information about life in the internment camps, the demographic and social transformation of the Little Tokyo neighborhood of Los Angeles, the practice of book collecting, and the spread of texts and artifacts from East Asia to the United States in the years immediately following World War II.

Ever the collector, and with an awareness that the correspondence might prove interesting to future scholars, Mr. Hawley saved the letters he received from Dr. Suski and interfiled them with carbon copies of his own typewritten replies. The collection was kept intact beyond the deaths of the two parties (Dr. Suski in 1960, and Mr. Hawley in 1987), by his granddaughter, Frances Seyssel—my mother—who inherited Mr. Hawley’s estate, including his library and small publishing company, Hawley Publications. By this time, the families, which had once been quite close, had drifted apart and were virtually unknown to each other.

In 2004, a reunion of sorts occurred when Dr. Suski’s great-granddaughter, Lauren Suski, emailed my mother:

My great grandfather is Peter Marie Suski. He wrote My Fifty Years in America. Is the book you are selling in English? Please let me know as I am interested in purchasing it. My family has several copies of the original book in Japanese. We have wanted to translate it for some time now. Thanks.

Lauren Suski had located what she thought was simply the publisher of her great-grandfather’s books, not knowing the long history between the two men. Yet my mother, who had found the letters tucked away on a basement shelf, was elated to discover that the Suski family was still located nearby in the Los Angeles area, and she set to work reviving and sharing those memories which had previously been lost. Lauren Suski and family, including her father, Dennis, and grandfather, Joe, among others, visited the Hawley house that is referenced in the letters, and which Joe himself remembered visiting as a child. Ms. Seyssel shared the correspondence with the Suski family, who had been completely unaware of its existence, and gave Dr. Suski’s originals to them to keep as part of their own family heritage. She made several full copies of both sets at that time.

Ten years later, when I began working with the copied letters for this project, I knew that I would need to obtain copyright permission from Dr. Suski’s descendants in order to digitize them. I also wanted to locate the originals to ascertain whether I could photograph them directly to create an online archive of digital facsimiles. Yet, despite the reunion which had occurred in 2004, the families had once again drifted apart—email addresses changed, some people moved, while others had passed away. Fortunately, the arrival of social media meant that, with some help from Google and Facebook, I found Lauren Suski and reunited the families for the second time.

Lauren recalled meeting my mother and remembered the letters but had never looked closely at them. It turns out that the box of letters had been misplaced among the belongings of Joe Suski, who had died in 2011, and she was not entirely sure where they now were (though she assured me, they were somewhere). It was not until I provided Lauren with a PDF copy of the correspondence that she was first able to read the words of her great-grandfather, as written to my great-grandfather.

As she read, I read. I read first with an eye towards uncovering historical details. Then I read looking for what was left unspoken and unacknowledged. I recognized traces of my own family history, and found myself becoming uneasy with the private revelations from Dr. Suski, as though I should not be intruding in these intimacies. But more than anything, I began to understand the complexity of these two men and their relationship with each other and the world. These letters are filled with the hopes and realities of two tumultuous lives, lives with which I am now closely acquainted. Perhaps not surprisingly, the personal nature of this project has both heightened my investment in it and has caused me to consider more deeply the affective nature of archival research.

The title of this thesis is drawn from Dr. Suski’s name for his quarters at the Heart Mountain internment camp, “Yellow Dust Abode.” The text of his explanation for the name is transcribed below and reproduced in figure 1.

He writes:

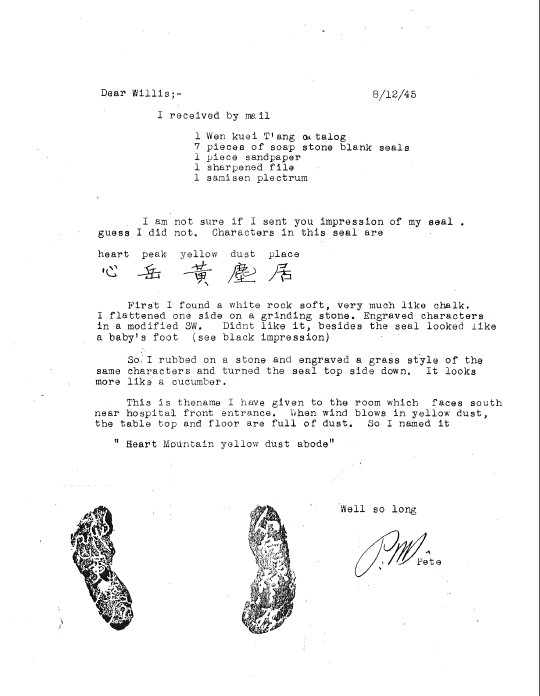

I am not sure if I sent you impression of my seal. Guess I did not. Characters in this seal are

heart peak yellow dust place

First I found a white rock soft, very much like chalk. I flattened one side on a grinding stone. Engraved characters in a modified SW. Didn’t like it, besides the seal looked like a baby’s foot (see black impression)

So I rubbed on a stone and engraved a grass style of the same characters and turned the seal top side down. It looks more like a cucumber.

This is the name I have given to the room which faces south near hospital front entrance. When wind blows in yellow dust, the table top and floor are full of dust. So I named it

‘Heart Mountain yellow dust abode’