Work for hire: Library publishing, scholarly communication, and academic freedom

What is the relationship of the librarian to the institution that employs her?

There are certain expectations of workplace allegiance that surpass professional autonomy and even the notion of academic freedom. By this I mean the extent to which you are expected to shill for your employer. It’s one thing to shy away from “biting the hand that feeds you” but it is quite another to become a booster for your institution. So what happens when library outreach crosses over from publicizing the library—its collections and services—and dips into praising the university? Are they, in fact, separable?

Recently I sat in on a talk from Jennifer Guiliano, delivered as part of a digital humanities speaker series at NYU Libraries, which made me think about whether librarians tend to identify with their institutions more readily than other academics. This might be expected if one considers the collections on which we expend so much time and energy—and the collaborative way in which we are accustomed to working. Yet I wonder if we could attribute this to the presence (or absence) of faculty status for librarians.

For if librarians are not faculty, they must be staff. Which means the work they do is considered “work for hire” as far as copyright goes (presuming there is no collective bargaining agreement to say otherwise), right? And without a personal investment in our service and scholarship outside of its institutional value, who is to say where the line between library and librarian is? After all, as many have pointed out: even our professional organizations cohere around libraries, not librarians. So if we’re going to expand the notion of what labor is valued in the academy, we should probably also be mindful of who owns our labor output. (The very idea that there might be a “teachers exception” to the copyright law for scholarly publications makes a pretty good case for librarian faculty status, if you ask me.)

After Guiliano expressed her frustrations about wrangling foundations and institutions only to have the lion’s share of a grant eaten away by overhead costs that far exceed the actual costs of a humanities lab, she told a familiar story. How many times, she asked, have you been approached by the university’s development office, or the marketing & communications department, with a request for feel-good stories about new projects, or public scholarship, or—better yet—examples of faculty-student collaboration that they could showcase to potential donors or prospective students and their families? How many times have they enthusiastically publicized your team’s work and collected the accolades, while continuing to cut the funding and resources available to do that very work? The institution is more than willing to reap the prestige of successful grants and digital projects, but when it comes to financially and structurally supporting the sustained work of the individuals behind them? Well, you know the story.

Some might call that story exploitation. But I digress.

“The Academy in the form of the libraries … can no longer support us as they once did.” —Singerman, RBS lecture (33:27)

I returned to my notes from Guiliano’s talk after attending a different lecture, given by Jerome E. Singerman (University of Pennsylvania Press) at Rare Book School just a few weeks ago. This talk was titled, “Scholarly Publishing at the Crossroads: or, How Do We Move Forward Without Getting Run Over?” and RBS has generously made the audio recording available online.

Singerman was focused on university presses and the declining sales of print monographs in the humanities, but his comments brought me back again to this question of individuals and institutions. At one point, as noted above, he portrays libraries as instruments, or proxies even, of an academy that has failed to support university presses and, by extension, the scholarly publishing system. Oddly, that’s a somewhat refreshing construction, considering the amount of self-blame that goes around in libraryland.

But what about the way that the academy was supporting the system outside of the library? Singerman surprisingly writes off the possibility of changing promotion and tenure requirements, despite his acknowledgement of the dire effect that the academic job market crash of the early 1970s had on scholarly publishing. It was then that academics, he explains, began to face “new and extreme pressures to publish earlier, more often, if they wanted to have a chance to enter, prosper, move upward in the academy” (29:45). Let me repeat that: “If they wanted to have a chance to enter.” So instead of a system whereby universities absorbed publication costs (i.e., author payment) through faculty remuneration, scholarly publication essentially relies upon a massive amount of hope labor. And who reaps the rewards? Certainly not the scholars who are made to front hundreds of dollars to provide copies of their own book for the tenure review committee.

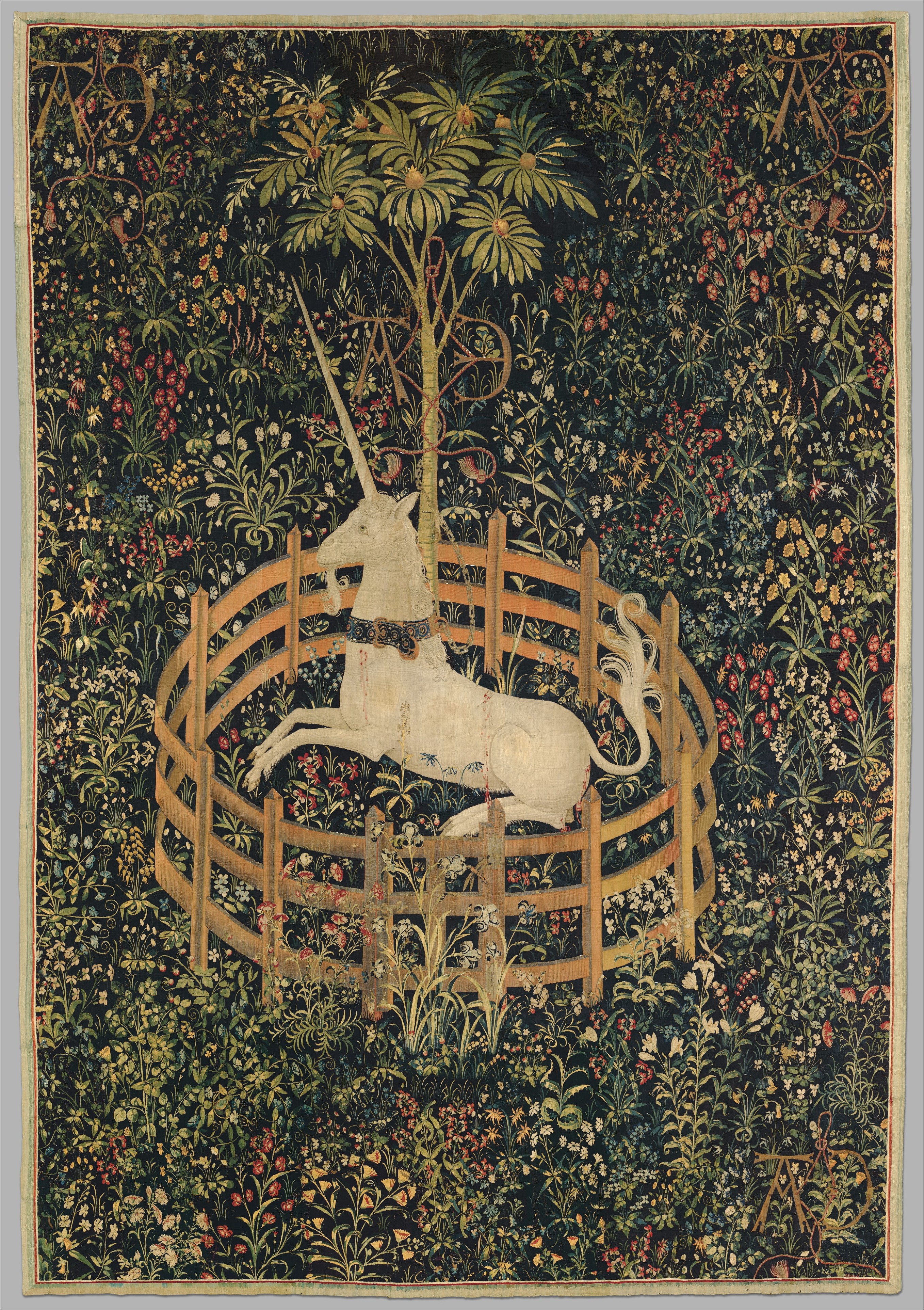

But it’s not only the hope labor of aspiring authors professors that masks the university’s abrogation of its share of scholarly publishing costs. It’s the libraries that rely on unpaid internships or unicorn librarians to conceal the damage that’s been wrought by disappearing staff lines. I’m reminded of Bethany Nowviskie’s comments about what happens when librarians value self-effacing service over honest engagement with their faculty colleagues:

With the best of intentions, it can lead to a strategy of hiding the messy stuff, or laying a smooth, professional veneer over increasingly decrepit and under-funded infrastructure.—Bethanie Nowviskie, “Fight Club Soap”

Under-funded infrastructure. Exploitation. That’s what this is about.

In his talk, Singerman took aim at three forces working to change the system of scholarly publication: the open access movement, the digital humanities “juggernaut,” and—as he termed them—”scholarly commons sites” that are “administratively located in the the library,” by which I’m assuming he meant institutional repositories. (37:00)

Those are not uncommon targets, necessarily, but there was something ominous about the way that he described the creation of “OFFICES OF SCHOLARLY COMMUNICATION,” as though it were newspeak for censorship. Now, this is not meant to be an in-depth critique of Singerman’s lecture, nor even is it meant to be a formal response to it. Instead, I want to think through why this notion was so troublesome to me. I’m genuinely perturbed and, frankly, perplexed by any perceived collusion between library publishing/scholarly communication initiatives and attacks on academic freedom. (Although, considering the sorry state of academic freedom at public institutions these days, I suppose I shouldn’t be surprised.)

But the real jaw-dropping moment of this talk was yet to come.

Having gestured towards a more sinister motive behind the establishment of scholarly communication as opposed to scholarly publishing, Singerman suggested that library scholcomm initiatives merited “a concern … that by placing their work on institutionally-based open access sites, employee faculty members—’employee faculty members’—may be ceding proprietary rights to their own scholarship, undermining their academic freedom.” (45:25)

So that’s it. I’m flummoxed. Floored.

Librarians are a profession with a code of ethics that encapsulates a commitment to intellectual freedom; how then could we be lumped in with corporatized university administrators who want only to extend the institutional brand?

Oh right. We did that. By selling the IR to the university based on its “institutional” branding over its value as a public good. So while I discreetly pick my jaw, along with the rest of me, up from the floor, I’m starting to wonder if Singerman is right. Or, rather: what structure is in place to prevent such a scenario from occurring? What happens if when our distinguished professors are replaced with “employee faculty members”? Are we doing enough to safeguard our systems from becoming tools for further exploitation?

At my library, the librarians are faculty (albeit, faculty who’ve been working without a contract for the last five years). I have to believe that this status shield would allow them to advocate for and build a sustainable, inclusive, and accessible system for scholarly publication. But we all know that those salary lines are disappearing more and more each year. Who’s to say IRs won’t one day fall under the umbrella of, say, enterprise IT?

Which has me asking, just who IS the university?